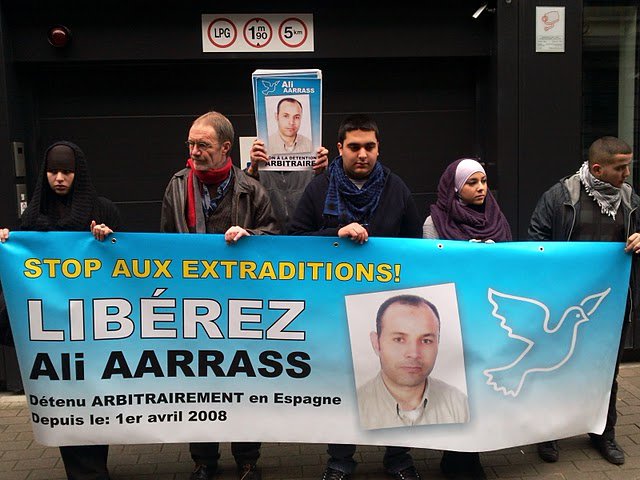

Dual nationals, equal rights and the case of Ali Aarrass

By IRR European News Team

14 December 2010, 2:00pm

European citizens of Moroccan origin fear that counter-terrorism cooperation with Morocco creates a second-class citizenship and denies dual nationals their human rights.

In a prison cell in Madrid, Spain, a 45-year-old Belgian-Moroccan dual national is currently on hunger strike. Only an interim measure imposed by the United Nations Human Rights Committee on 26 November 2010 temporarily prevented Ali Aarrass from being extradited from Spain to Morocco – a forced removal that is still imminent. But why has the case of Ali Aarrass become critical to European Muslim citizens of Moroccan origin living in Spain and Belgium?

Who is Ali Aarrass?

Ali Aarrass is a naturalised Belgian citizen of twenty-one years’ standing, who was born in the Spanish city of Melilla, a small Spanish enclave in the north of Morocco. In 2005, after living in Belgium for twenty-eight years, Ali Aarrass decided to return to Melilla to live and work alongside his father. And it is there that he was first arrested in 2006 and accused (though never charged or brought to trial), alongside a Spanish-Moroccan national, Mohammed el Bay, of being part of a network smuggling guns to Morocco, and threatened with extradition to Morocco. The Muslim community of Melilla, as well as the president of Melilla, and his local government led by the Partido Popular (PP), the Coalition for Melilla (CPM, the most important party of the opposition), the Islamic Commission for Melilla and the Association Inter Culture Party, immediately united against the men’s extradition (successfully in the case of Mohammed el Bay, who was released in November 2010). Abderramán Benyahia, the spokesperson for the Islamic Commission of Melilla, declared that if the two men had been named ‘García or Pérez, neither the National Court nor the Government would consider their extradition’.

Security of Muslim European citizens undermined

The fact that the Melilla alliance has maintained cross-party parliamentary support for Ali Aarrass and Mohammed el Bay since 2006 speaks volumes about the levels of distrust Spanish Muslims in Melilla feel for their own politicians and government. For what they have grounds to fear is that because of their north African origins (the Moroccan government does not allow its citizens to renounce nationality save in exceptional circumstances and by royal decree), the Spanish government will betray them, by removing them from the protections associated with Spanish nationality and ‘convert them’ for all practical purposes into Moroccan citizens. This mistrust Spanish Muslims feel for their own government is shared by Belgian Muslims of dual Belgian-Moroccan nationality, who particularly fear the implications of a 1997 treaty between Belgium and Morocco that allows dual Belgian-Moroccan nationals, who have committed a crime which carries a sentence of two years or more, to be extradited to Morocco. It is laws such as this, it is argued, that institutionalise second-class citizenship for Muslims, leaving dual nationals vulnerable to the long reach of authoritarian states and the torture practices of their intelligence services, in this instance that of Morocco’s notorious Directorate for the Surveillance of the Territory (Direction de la surveillance du territoire, DST).

In all the campaign literature to free Ali Aarrass, Spanish and Belgian Moroccans express the same anxieties and mistrust. ‘The Socialist government is telling us that we are not Spanish, after twenty-five years here we remain Moroccan nationals with Spanish citizenship,’ argues Abderramán Benyahia of the Islamic Commission of Melilla, adding that they are not the playthings, the ‘merchandise’ of the Spanish and Moroccan governments. Belgian dual nationals experience exactly the same second-class citizenship status every time they go abroad, argues Farida Aarrass, Ali’s sister, who lives in Brussels and is the spokesperson for the Free Ali campaign. ‘Belgian-Moroccan dual nationals feel no sense of security anywhere because as soon as they have left Belgium, no consular assistance is provided to them,’ she told the London Support Committee (LSC) to Stop the Extradition of Ali Aarrass, that quickly gained the support of 56 human rights lawyer (including four QCs), professors, MPs and MEPs when it was formed in November 2010. Farida Aarrass told the LSC that despite her repeated requests to the Belgian government to intervene to protect Ali Aarrass, its own citizen, the government has pointedly refused either to protect her brother from extradition to a country that practises torture, or to monitor the conditions of his detention in Spain. When Green Party MP Zoe Genet tabled a parliamentary question, the minister merely replied that the Belgian government had full confidence in the Spanish authorities to deal fairly with Ali Aarrass.

And Belgian-Moroccan dual nationals’ sense of insecurity will be heightened by a recent proposal by Popular Party deputy Laurent Lois for a points system for the withdrawal of nationality from naturalised Belgians and dual nationals. They would start with a ‘credit’ of ten points, and then points would be lost for every criminal offence, so that at zero they ‘lose their Belgian nationality and will be sent back to their country of origin’, said Lois on his Facebook page.

Double standards

From day one the refusal to guarantee European Muslims of Moroccan descent equal rights and fair treatment before the law, has been reflected in the treatment of Ali Aarrass. For four years now, Ali Aarrass has been lost in the Kafkaesque world of anti-terror laws which were set in place after the events of September 11. In such a world neither the innocence or guilt of Muslim terror suspects can be legally established, as the laws deny Muslims due process and guilt is applied by association.

Ali Aarrass was first placed under investigation by the Spanish National Criminal Court in 2006 on suspicion of being in possession of a weapon that was part of a set of weapons due to be smuggled into Morocco. The judicial investigation put tremendous pressure on Ali Aarrass’ extended family, as he had previously been supporting his wife and young adopted daughter, as well as his step-brother who had gone blind. Nevertheless, Ali Aarrass’ father and the entire family pooled all their savings to secure his release, under caution, during the investigatory process.

This investigatory process went on for three years. Finally, in March 2009, the Aarrass family were informed that the Spanish National Criminal Court and the anti-terrorism judge Baltasar Garzón had provisionally closed its investigation due to lack of evidence implicating him in any act of terrorism. Ali Aarrass was neither charged with any offence in Spain nor brought to trial. But if the family thought that this meant the end of their ordeal, they were wrong. For despite all their efforts, Garzón then declared that he had no objections against Ali being extradited to Morocco to stand trial there on the basis of similar allegations. Hence, Ali Aarrass, who had been placed in administrative detention pending extradition to Morocco in April 2008, was to remain detained for another two years in Spain. To an appeal by his lawyer that his extradition would constitute double jeopardy, ‘ violat[ing] the legal principle that you cannot judge a person two times for the same offence’, the Spaniards answered that Ali Aarrass was never brought to trial in Spain, and there is no law against being investigated twice for the same offence.

Building intelligence links with a torture state

One particularly worrying aspect of this case is that it comes at a time when the Spanish government, in the name of combating the terrorist atrocities of Casablanca and Madrid, is seeking closer counter-terrorism ties with Morocco, despite Morocco’s record of human rights abuse, torture, and unfair trials. A special unit of the Spanish and Moroccan intelligence services was set up in 2006 to exchange information, as anti-terrorist judge Garzón declared that Morocco and Spain must set aside their differences since ‘Morocco is the worst terrorist threat for Europe’. Clearly, Garzón, and the Spanish government have ignored the reports of Amnesty International (AI), Human Rights Watch (HRW) and the Arab Commission of Human Rights and the findings of the UN Joint Study on Secret Detention, the Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly’s Committee for Legal Affairs and Human Rights’ report on Secret Detentions and Illegal Transfers of Detainees involving Council of Europe Member States. It has not been influenced by the European parliament resolutions concerning the CIA’s extraordinary rendition programme, where the role of torture in secret detention centres in Morocco has been laid bare. If politicians and legislators had read these reports carefully they would know that Morocco’s counter-terrorism efforts, and the actions of its intelligence service the DST, have been linked to human rights abuses arising from holding suspects incommunicado in unrecognised detention centres where torture and other ill-treatment are used as a means of extracting confessions. Among the most frequently reported methods of torture are beatings, the suspension of the body in contorted positions, and the threat of rape or other sexual abuse of detainees’ female relatives. Other reported methods include rape by the forced insertion of objects into the anus, sleep deprivation, cigarette burns, and the application of live electrodes to the body. In the UK, former Guantanamo detainee, Binyam Mohamed has recounted how for eighteen months the Moroccans held him in incommunicado detention, during which time they slashed the most intimate parts of his body with razors, burned him with boiling liquids, stretched his limbs causing unimaginable agony, and bombarded him with ferocious sound.

AI, HRW and the International Federation of Human Rights could also draw the Spanish government’s attention to Morocco’s judicial proceedings and human rights abuses against over 1,500 people suspected of involvement in the Casablanca suicide bombings of 2003 or association with ‘violent acts attributed to Islamist groups’. Human rights groups monitored these proceedings and found that hundreds of those sentenced were allegedly tortured in custody, with dozens sentenced to death on the basis of forced confessions. AI and HRW accused Morocco of holding suspects incommunicado in an unrecognised detention centre, believed to be the Témara detention centre, which is located in a forested area about 15 kilometres from Rabat, where the DST intelligence services have their headquarters, and where detainees were allegedly subjected to torture or other ill-treatment.[1]

Guilt by association

But it was a trial ending in July 2009 that was given as the raison d’être for Ali Aarrass’s re-arrest on the basis of a Moroccan international arrest warrant which made similar accusations as before, but this time added possible involvement in the Casablanca bombings (Ali Aarrass was living in Belgium at the time) and belonging to the so-called ‘Belliraj cell’. This was a reference to Abdelkader Belliraj, a 52-year-old Moroccan-born Belgian resident of dual nationality who was the alleged ringleader of a plot said to involve thirty-four other individuals, including a television journalist and five senior members of political parties that profess their commitment to non-violence and democracy. These thirty-five individuals were arrested in February 2008 and accused of plotting to destabilise the state.[2] Yet their trial, which lasted for eighteen months at the Rabat Appeals Court in Sale, was monitored and immediately condemned as unfair by Human Rights Watch, the Arab Commission of Human Rights and Adala, a Moroccan organisation promoting the right to a fair trial[3]. The organisations claimed that confessions were falsified or obtained through torture,[4] and that the trial was used as a cover for clamping down on the legitimate activities of non-violent Islamist political parties. And in December 2010, in another twist, Wikileaks published a secret communication, made shortly after the conclusion of the trial by the American ambassador in Rabat to the State Department in Washington and to American ambassadors in Europe in which the ambassador repeats the criticisms of human rights organisations regarding the trial, accuses the Moroccans of using their anti-terrorist laws to marginalise Islamist political groups and quotes the opinion of the Counselor at the Belgian embassy who judged the trial ‘unfair’ and ‘pre-cooked’.

Violette Daguerre of the Arab Commission of Human Rights observed that all those arrested ‘insisted in front of the court that they suffered violent interrogation and that confessions were obtained under torture’. She observed that many of those who faced trial seemed to be there simply because they knew Abdelkader Belliraj.

From extraordinary rendition to administrative rendition

What is also disturbing about the treatment of Ali Aarrass by Belgium and Spain is that it comes at a time when a growing number of European politicians are trying to distance Europe from the CIA’s discredited extraordinary rendition programme, in which Morocco played a key part in the torture of Binyam Mohammed (British) and Abou Elkassim Brital (Italian). What the case of Ali Aarrass suggests is that the European authorities are now prepared to establish a system of administrative rendition, which avoids the illegality of the extraordinary rendition programme while achieving the same result – namely, sending Muslim terror suspects back to countries where they will face cruel and degrading treatment, torture, and possibly the death penalty, in violation of the non-refoulement principle. Apparently, human rights standards do not apply to Muslim terror suspects.

On learning of the UN stay on his extradition, and that support campaigns were now active in Melilla, Brussels and London, Ali Aarrass told his wife to relay to his supporters the message that ‘hope now reaches me through your voice, the hope that it is not too late and that the judgements will be overturned’. For over two years now, Ali Aarrass, against whom no evidence has been produced linking him to any act of terrorism, has been imprisoned within a high security regime reserved for terrorism suspects. In his message to supporters he vowed to continue his hunger strike. ‘I have been in arbitrary detention for far too long. I’m not asking Spanish justice to have compassion for me; but I have been deprived of my freedom for two years, and each day that passes, each hour, each minute has become unbearable to me. I am not going to end my hunger strike until justice is given back to me. My freedom is my due.’

Endnotes: [1] See Human Rights Watch, ‘Morocco: Human Rights at a Crossroads’, October 2004; Amnesty International, ‘Morocco/Western Sahara: Torture in the Anti-Terrorism Campaign: The Case of the Témara Detention Centre’, MDE 29/004/2004, June 2004; International Federation of Human Rights, ‘Les autorités marocaines à l’épreuve du terrorisme – la tentation de l’arbitraire.’ No 379, February 2004. [2] The Brussels Appeal Court initially ruled against the Moroccan extradition request of dual Belgian-Moroccan nationals on the grounds that it was clearly made for ‘political reasons’ and even the Belgian security services doubted the ‘relevance’ of the information provided by their Moroccan counterparts. [3] See Human Rights Watch, ‘Morocco: Address Unfair Convictions in Mass Terror Trial,’ 29 December 2009. [4] In a letter to his Belgian lawyer Vincent Lurqin, Belliraj said that his interrogators held him incommunicado, blindfolded and beat him, hung him upside down by his feet and subjected him to electric shocks.You can email the London Support Committee to Stop the Extradition of Ali Aarrass at: londonaliaarrass@gmail.com.

The Institute of Race Relations is precluded from expressing a corporate view: any opinions expressed are therefore those of the authors.

Moroccan man forcibly returned by Spain could face torture

Moroccan man forcibly returned by Spain could face torture