Ali Aarrass has been tortured

(Communiqué de presse Jus Cogens : translation by the London Support Comittee for Ali Aarrass, BM Box 8784, London WC1N 3XX. Tel: 07879 687 390. Email: londonaliaarrass@gmail.com)

(Communiqué de presse Jus Cogens : translation by the London Support Comittee for Ali Aarrass, BM Box 8784, London WC1N 3XX. Tel: 07879 687 390. Email: londonaliaarrass@gmail.com)

Since Spain’s extradition of Ali Aarrass to Morocco contrary to the suspension request of the UN Human Rights Committee, the Belgian-Moroccan Aarrass has been tortured in Morocco.

Ali Aarrass is Belgian-Moroccan. He is Moroccan only by virtue of the fact that he had to obtain an identity card to travel. Ali Aarrass was born in the Spanish enclave of Melilla. He has never lived in Morocco and has no effective ties with that country. He has lived in Belgium for 28 years, he did his military service there, and it was there he developed a local business and deep attachments.

Ali Aarrass has a clean record both in Belgium and in Spain, where he returned in his father’s footsteps in 2005. The object of two investigations in Spain into whether he had any links with terrorist groups, he was completely cleared after an investigation lasting nearly three years, led by judge Baltasar Garzon. But he was detained in Spain from 2008 pursuant to an extradition request from the Moroccan government, who suspected him of membership of the ‘Belliraj terrorist cell’.

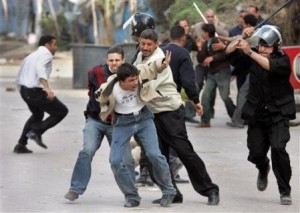

It is common knowledge that Morocco systematically uses torture in the fight against terrorism, invoked by the state to suppress all peaceful political opposition. It is also common knowledge that the Belliraj trial which took place in Morocco was a charade, a travesty of justice, where the defendants were tortured, then condemned on the basis of their own ‘confessions’, obtained by torture. On this issue, the criticisms of international human rights organisations are just as strong as those expressed in relation to other countries of the Maghreb, now in open revolt.

Ali Aarrass always fought hard against his extradition. He went on hunger strike three times to try to stop it. But despite requests from his family, the Belgian minister of foreign affairs refused to contact the Spanish authorities, even to register the concerns of the Belgian authorities about a national of the country. The minister invoked the ‘mutual confidence’ between European states, although such confidence appears misplaced in this instance.

On 19 November 2010, the Spanish Council of Ministers approved Ali Aarrass’s extradition. By contrast, Spain refused to allow the extradition of M El Bay, detained in relation to the same affair but with Spanish-Moroccan nationality. This man has quite rightly been freed.

The United Nations Human Rights Committee was urgently requested to intervene to stop the extradition. To the family’s great relief, the Committee issued an interim measure requesting Spain not to proceed with the extradition, on 26 November 2010. Those close to Ali Aarrass believed that the injustice which he had suffered for years was about to end.

But unhappily, on 14 December, the Belgian consul, who had finally received instructions to visit M Aarrass, was told the visit could not take place: Ali Aarrass had been extradited. The consul did not bother to tell Ali Aarrass’s lawyers or his family. It was through the press that the news of Ali’s extradition became known to his family.

In extraditing Ali Aarrass in spite of the UN Human Rights Committee’s interim measure, the Spanish government is clearly acting in breach of its international obligations. Its action is even more shocking in the light of its request to the Committee on 7 December to have the interim measure lifted, a request which was denied.

After the illegal extradition, the Belgian minister of foreign affairs was once more contacted. This time, the minister hid behind Ali Aarrass’s dual Belgian-Moroccan nationality to decline all intervention on his behalf. This refusal is unacceptable. Morocco may eventually decline the requests of the Belgian consular authorities, but this does not absolve Belgium of its own diplomatic obligations, and international pressure of this type is likely in itself to protect Ali Aarrass.

Numerous steps were taken, from 16 December 2010, to locate Ali Aarrass and to support him. The Moroccan minister of was advised of Ali Aarrass’s precarious state of health (he had been on hunger strike for nearly a month), and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture was also alerted because of the fear of ill-treatment.

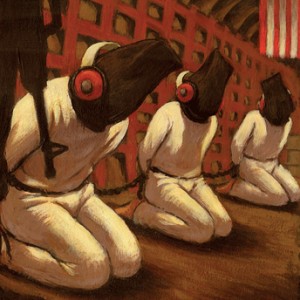

Unhappily, Moroccan law permits close detention for up to twelve days in cases involving terrorism, and suspects are held incommunicado during this period, with no access to lawyers or to the outside world. In its report of 1 December 2004, the Human Rights Committee had already indicated that ‘We consider the period of close detention too long – 48 hours (renewable once) for ordinary crimes and 96 hours (renewable twice) for crimes connected with terrorism, during which time suspects may be held without being brought before a judge. The State Party should review its legislation on close detention and bring it into conformity with the provisions of Article 9 and with all the other provisions of the Covenant [on Civil and Political Rights]. The State Party should amend its laws and its procedures to allow persons arrested to have access to a lawyer from the beginning of his detention (Articles 6, 7, 9, 10 and 14 of the Covenant).’

It was during the course of this illegal detention that M Aarrass was tortured. He was deprived of sleep for many days and subjected to incessant questioning. During this period, he claims he was forcibly injected with chemical substances, had electric shocks to his genitals, was raped with a bottle and was subjected to numerous other unspeakable tortures.

It appears that when he was finally brought for the first time before the examining magistrate, M Aarrass was in such a bad state that the hearing could not proceed. The second time, M Aarrass’ lawyer accompanied him, but the examining magistrate refused to record the torture allegations.

The Convention Against Torture and Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment of 10 December 1984 imposes these obligations:

‘Each State Party shall ensure that any person who claims to have been subjected to torture on any territory under its jurisdiction has the right to bring a complaint to the competent authorities of that State, which must proceed promptly and impartially to examine the case. Measures must be taken to protect the complainant and any witnesses against ill-treatment or intimidation as a result of making the complaint or statement.

‘Each State Party shall ensure that no statement which is established to have been obtained by torture is used in any proceedings, except against the person accused of torture to establish that the statement was made.’

In these circumstances, Ali Aarrass’ family and friends are extremely concerned. They are afraid that Ali will be condemned on the basis of statements obtained by torture, from him and from M Belliraj. The Moroccan police file contains no objective evidence which could implicate M Aarrass in any terrorist group.

The family and friends of Ali Aarrass call on the Spanish and Belgian governments to concern themselves over the person they have delivered into the hands of torturers. They demand a prompt and impartial inquiry into these allegations of torture. They call on all persons of goodwill to exert pressure to ensure that Ali can enjoy a fair trial. They implore the Moroccan judicial authorities not to condone the practice of torture and to render justice of a kind which can honour the Moroccan people.