‘Citizenship is man’s basic right, for it is nothing less than the right to have rights.’ Chief Justice Earl Warren, dissenting in Perez v Brownell, US Supreme Court (356 US 44 1958).

‘Citizenship is man’s basic right, for it is nothing less than the right to have rights.’ Chief Justice Earl Warren, dissenting in Perez v Brownell, US Supreme Court (356 US 44 1958).

It is probable that Chief Justice Warren had read Hannah Arendt’s ground-breaking study The Origins of Totalitarianism. Arendt coined the phrase ‘the right to have rights’, which encapsulated her insight that although human rights were held to be universal, access to those rights was impossible without citizenship of a nation state.

The relationship between a Government and its citizens, the obligations owed by the one to the other, and how and for what reasons Governments can end the relationship by revoking citizenship have become fraught questions in the post-9/11 age, when citizens’ rights have repeatedly crashed against doctrines of State sovereignty. Some Muslim citizens of European States have discovered that they cannot rely on their Government to protect them from arbitrary and illegal detention or torture abroad. Others have discovered how easy it is to lose citizenship, and how few procedural protections they have.

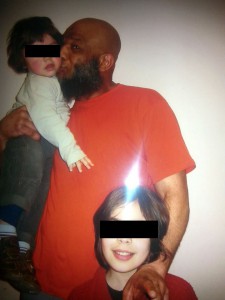

The case of Ali Aarrass

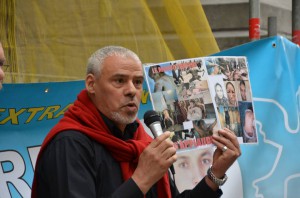

On 10th January 2014, lawyers appeared before the Brussels first-instance court to argue that Belgium is in breach of its obligation to protect its dual-national citizens from torture. The case is that of Ali Aarrass, a Belgian-Moroccan citizen tortured and imprisoned in Morocco, to whom the Belgian Government refuses to extend consular protection.

Born in the Spanish enclave of Melilla and educated in Belgium, where he did his military service, Ali was subjected to a two-year investigation for alleged involvement in arms smuggling by Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón, and was cleared in March 2009. The Spanish authorities nevertheless extradited him to Morocco in December 2010, despite a UN Human Rights Committee request to stay the extradition. Ali disappeared into incommunicado detention and nearly a year later was convicted in the Rabat court of smuggling arms and sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment (later reduced to 12). The conviction was based solely on ‘confession’ evidence which Ali consistently maintained was false, his signature to an incomprehensible document in an unfamiliar language obtained by sustained torture.

The allegations of torture were never properly investigated by the Moroccan authorities, but following a prison visit with a forensic medical expert in September 2012, UN Special Rapporteur Juan Mendez confirmed that Ali had been severely tortured. A December 2013 report from the UN’s Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concurred that Ali’s confession was obtained by torture, rendering his conviction and imprisonment unlawful.

No help from Belgium

During the whole period of his incarceration, Ali’s family and supporters have called on the Belgian Government to provide diplomatic protection. The Foreign Minister has consistently refused, saying that in Morocco, Ali is a Moroccan citizen and it would be contrary to normal practice to intervene diplomatically. Only in August 2013, when Ali was in a critical condition on a hunger and thirst strike, did the Minister ask the Moroccan Government to ensure that he was treated with respect for his human rights. Even then, he insisted that the Government was not providing diplomatic assistance and would not intervene in the conviction. The lawyers’ argument is that since torture is jus cogens in international law, the obligation to protect citizens from torture must take precedence over diplomatic conventions of non-intervention.

What is citizenship worth?

What is citizenship worth?

Ali’s case raises forcefully the issue of the way Muslim ‘terror suspects’ are treated as non-citizens by the States of their nationality, in the context of the clash between diplomatic conventions (reflecting State sovereignty) and human rights obligations.

Feroz Abbasi was one of the Muslim British citizens kidnapped abroad and bundled off to Guantánamo (others included Ruhel Ahmed, Tarek Dergoul, Jamal Al Harith, Shafiq Rasul, Asif Iqbal, Richard Belmar, Martin Mubanga and Moazzem Begg). In a challenge brought on behalf of Abbasi, R (Abbasi) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs [2002] EWCA Civ 1598, the Court of Appeal accepted that at Guantánamo the men were ‘arbitrarily detained in a “legal black-hole” without the possibility of challenging their detention, in apparent contravention of fundamental principles recognised by both jurisdictions and by international law’i – but the Government denied any entitlement to consular protection against arbitrary and limitless detention – and the court agreed. ‘International law has not yet recognised that a State is under a duty to intervene by diplomatic or other means to protect a citizen who is suffering or threatened with injury in a foreign State’, the Court of Appeal said. The judges held that since the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (FCO) had already considered Mr Abbasi’s request for assistance, there was nothing further they could do – they could not order the FCO to intervene on behalf of the Britons held at Guantánamo.

Relatives of Moazzem Begg and other British detainees sought to join Abbasi’s case as interveners and to put evidence of their treatment before the Court, but the application was refused, so there were no allegations of torture or inhuman treatment before the Court, although by the time of the hearing in September 2002 the treatment of detainees (including British nationals) at Bagram and Guantánamo was already causing grave concern.

It is not only Muslims who find themselves abandoned by the country of their nationality in the face of ill-treatment by a foreign State. As recently as January 2014, the European Court of Human Rights in Jones and others v United Kingdom [2014] ECHR 32, upheld the refusal by the UK House of Lords in 2006 to allow four white Britons to sue their Saudi torturers in British courts. But it seems that only in the case of Muslims do Governments collude in torture and illegal rendition. The report of the aborted Gibson inquiry, The Detainee Inquiry, published in December 2013, indicated that from early 2002, British intelligence officers were aware of ill-treatment including the use of hoods, stress positions, sleep deprivation and physical assaults on detainees including at least one British national; that some approved of the ill-treatment, others turned a blind eye, and that even when officers registered concern, no action was taken to stop it. Similarly, the UK did not take opportunities to object to proposals to transfer individuals including British nationals to Guantánamo, and in some cases approved or cooperated with US renditions to torturing states. Ministers only sought the release of British detainees from Guantánamo in December 2003.

Extradition: Talha Ahsan’s case

British citizenship provides no protection against extradition, either. In October 2012, British citizens Babar Ahmad and Talha Ahsan (who has won prizes for his poetry) were extradited to supermax incarceration in the US, to await trial on charges which the Director of Public Prosecutions refused to prosecute in the UK for lack of evidence and whose sole connection to the US is a computer server’s location. The Asperger’s syndrome which Talha suffers, in common with Gary McKinnon, and which moved Home Secretary Theresa May to stop McKinnon’s extradition, did not help Talha.

Getting and losing citizenship

The protection of citizenship is becoming increasingly threadbare for European Muslims. Simultaneously, in the UK at least, citizenship has become harder to acquire, and easier to lose. In 2002, with multiculturalism giving way to the new politics of ‘community cohesion’, the New Labour Government made naturalisation more difficult. Prospective citizens were tested to ensure that they were familiar with ‘British values’, to which they pledged allegiance in a revamped citizenship ceremony under the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Until 2002, only British citizens who had become British by naturalisation or registration (as opposed to being born British) could lose citizenship, and a strict procedure for revocation of citizenship had to be applied before the loss of citizenship took effect. The new law stipulated for the first time that those born British could be stripped of their citizenship, provided that they would not become Stateless. It did away with the old grounds for deprivation of citizenship, disaffection or disloyalty, and trading with the enemy, replacing them by ‘conduct seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK’. With no definition of ‘vital interests’, the new law potentially embraced a much broader range of actions for which citizenship could be forfeit.

Concerns at the vagueness of the phrase are heightened by the extreme breadth of the cognate phrase ‘national security’ and the discretion given to ministers to define it. Successive Governments have decided that actions against a ‘friendly State’ can damage the UK’s national security, no matter that we cannot choose our Government’s friends, who include many torturing states. Senior judges have both accepted this broad definition and have left it up to ministers to decide whether particular actions damage national security. ‘The courts are not entitled to differ from the opinion of the Secretary of State on the question of whether, for example, the promotion of terrorism in a foreign country by a UK resident would be contrary to the interests of national security’, said Lord Hoffmann in 2002 in the case of Shafiq ur Rehman v SSHD [2003] 1AC 153. There is no reason to believe that the judges would be any less deferential on the question of what are the UK’s ‘vital interests’ and what conduct would be ‘seriously prejudicial’ to them. In any event, since 2006, the only criterion for depriving a British citizen of his or her nationality is that it is ‘conducive to the public good’ to do so.

Loss of procedural protection

In 2004, the provision which allowed an appeal before the deprivation decision took effect was repealed, meaning that the person is no longer a British citizen from the moment the decision is served, and can (if abroad) be excluded from the country. Unsurprisingly, since 2004 virtually all deprivations have occurred while the ‘target’ is abroad, and the ‘target’ then excluded, creating untold difficulties for families, who must either share a husband or father’s exile or endure separation. In a recent case, L1 v SSHD [2013] EWCA Civ 906, the notice did not reach its target until the 28-day time limit for appealing had expired. The Home Office sought to strike out his appeal as late, and the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC) agreed that the man had lost his appeal rights. It was left to the Court of Appeal to expose the essential injustice of this position: waiting until the man left the country to ‘serve’ the notice of deprivation of citizenship without actually giving it to him, by sending it to the home address in the UK to which he could not return, was manipulation of the process to try to deprive him of appeal rights, the Court of Appeal held.

Appellants are unlikely even to know the detailed grounds for deprivation, or see the evidence relied on. Such was the case for at least forty applicants for naturalisation, who were refused on ‘character’ grounds, and were given no details. A five-year legal battle has left them no clearer as to whether the refusal rests on mistaken identity, or malicious allegations, or monumental misunderstanding as can be seen in the decision of AHK and others v SSHD [2013] EWHC 1426 (Admin). How much more of an injustice is it to strip someone of a citizenship they may have had since birth, without providing detailed reasons and detailed evidence which they may be able to rebut?

A New Labour Government was behind the deprivation provisions, but the Coalition Government has used them more. Five people were stripped of citizenship from 2003 to May 2010, and at least 37 since – 20 in the past year, according to the Bureau for Investigative Journalism, which, says that two of those who lost citizenship were then killed by drones, while one man, Mahdi Hashi, was taken by rendition to the USA.

Deprivation and statelessness

In October 2013 the Supreme Court ruled that Hilal Abdul-Razzaq Ali Al-Jedda could not be deprived of citizenship, as this would make him stateless. He had lost Iraqi citizenship when he became British. The Home Office argued that his statelessness would not be the fault of the Home Office but his own fault, for failure to re-apply for Iraqi citizenship. Following the Supreme Court’s rejection of the argument, the Home Office pushed through an amendment to the Immigration Bill on its third reading in the Commons in January 2014, to allow naturalised British citizens with no other nationality to be deprived of citizenship, thus rendering them stateless, for conduct ‘seriously prejudicial to the vital interests of the UK’.

The fact that the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness allows this, since the UK reserved this power when it signed the Convention, does not make it any less objectionable, particularly since it is partly politically motivated, a sop to far-Right Tories, and partly a riposte to the Supreme Court’s Al-Jedda judgment. The new clause 60 would allow the Secretary of State to take account of conduct pre-dating the Act, which shows the Government clearly has Al-Jedda in its sights, as well as Abu Hamza, another beneficiary of the current ban on rendering British citizens stateless.

The ‘right to have rights’ has become, in Theresa May’s words, a privilege, not a right. States’ rights are absolute; those of citizens are contingent and increasingly precarious.

For more information about Ali Aarrass and Talha Ahsan see www.freeali.be/ and freetalha.org/.

Frances Webber is a Vice-President of the Haldane Society. She is Vice-Chair of the Institute of Race Relations Council of Management and a former barrister who specialised in immigration, refugee and human rights law until her retirement in 2008. She co-edited Macdonald’s Immigration Law and Practice (5th edition, 2001, 6th edition 2005) and Halsbury’s British Nationality, Immigration and Asylum (4th edition, 2002 reissue), and is the author of Borderline Justice: the fight for refugee and migrant rights (2012).

Frances Webber is a Vice-President of the Haldane Society. She is Vice-Chair of the Institute of Race Relations Council of Management and a former barrister who specialised in immigration, refugee and human rights law until her retirement in 2008. She co-edited Macdonald’s Immigration Law and Practice (5th edition, 2001, 6th edition 2005) and Halsbury’s British Nationality, Immigration and Asylum (4th edition, 2002 reissue), and is the author of Borderline Justice: the fight for refugee and migrant rights (2012).

Dans la presse : Afriquinfos

Dans la presse : Afriquinfos Dans la presse : Yabiladi

Dans la presse : Yabiladi